Progress in planning has been slower than I’d like in this final chapter. I have noticed that I’ve been pushing myself mentally in the wrong direction. Like, it’s just stressful sometimes to insist on delivering instead of focusing on what’s in front of you. Even though I know what I want and have the stage set, and I’m looking forward to actually drawing this thing once I’m done, I’ve piled on enough distressed feelings in this particular chapter plan that it’s demotivating. That said, I have close to half the pages thumbed, and I’m going to be doing a fun action sequence next.

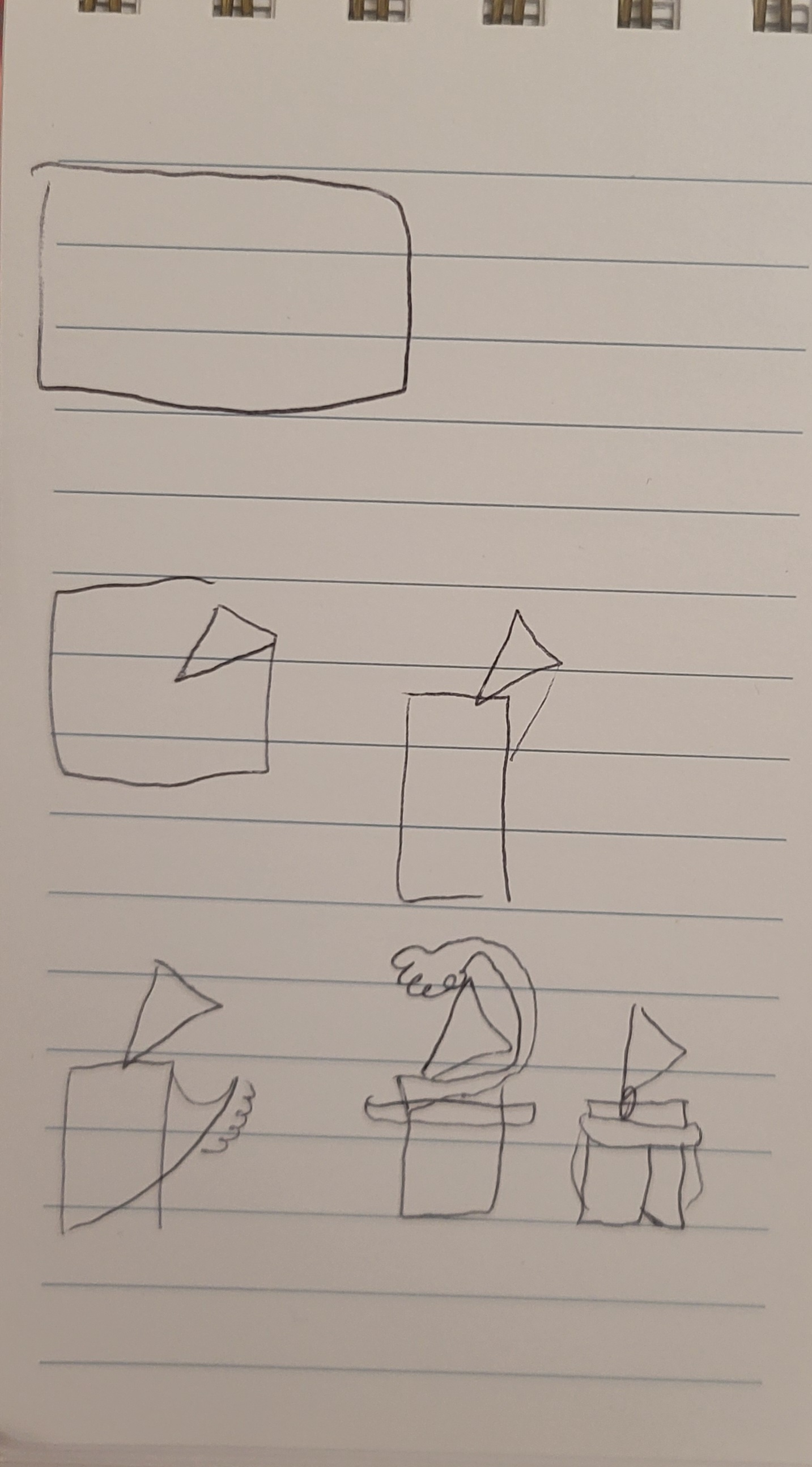

The picture posted with this is a sketch I drew trying to make sense of a traditional Libyan dress/wrap garment. I found it while looking into stuff for my Medusa design (fun fact: It’s possible that Medusa comes from Amazigh culture, adopted into Greek mythology through colonies in North Africa). I am having a hard time finding reliable reference for this garment because I don’t know its name. I drew this based on a video I found, which still left me with some questions. If you know what this is, please tell me what it’s called! I thought that was simple enough info to come across, but it hasn’t made its way to me yet.

Comics is a visual storytelling medium. While there’s obviously room for virtuosic talent – especially as it becomes necessary to execute on certain images or elements – the fundamentals needed to make good comics are clarity of action/moment, expression and gesture, and character design. That last one is what I want to talk about today. Good character design does a few things. First, it tells the reader something about the character. Genre tropes and other bits of visual grammar can help streamline the process. Wherever you get the design elements, you want the reader to immediately get an impression for the most important thing to know about that character. Second, good design is memorable. No matter how many characters you include in a story, you want the reader to be able to immediately recognize each of them. A fingerprint, something that is immediately and obviously “that character” that is apparent no matter how often that character is seen.

I have an example I want to talk about, from Murciélago by Yoshimurakana. It’s a dark horror/crime manga that I’ve read for a while. Really, truly one of the best things I’ve read. Among the many strengths that make this series great is the strong character design. It’s going past twenty volumes now, and across that time, a ton of characters have been introduced. While there are a number of very distinct and outlandish designs, there are also a lot of common, ubiquitous designs that are equally strong. Now, the issue with the example I want to talk about is that it’s a huge spoiler for one of the best storylines, and I really want to encourage you to read this book, so I’ll try to be vague but still get the point across.

There is a character in Murciélago who appears briefly in the early part of the series, and then shows up even more briefly later on. Small but important role. They are no one special; that’s the whole point. Their design emphasizes this, with no particular stand-out details or elements to latch onto or speak to some special quality. Just a person, living their life. When this character reappears, it’s in a full-page splash, a big and important moment. When I saw this, it took me a split-second to remember who it was, and it struck me like a lightning bolt. A massive shock, which immediately changed everything about the situation and added so much narrative and metanarrative. It had been literal years since I first saw them, and there’s no reason why I, or anyone, should remember this character, in particular. The story moment, sure, but you’d be forgiven for not recognizing who it is and get the OMG feeling as it’s unpacked on the following pages.

That’s what I mean about strong character design. To be able to immediately register a throwaway character as a specific person, such that they’re recognizable so long after they first appeared, is powerful. It makes you look at them differently, and realize that actually, there was a particular detail that registered this as a specific person for me. You go to their first appearance, and oh, yeah, this was a very short scene where this generic person feels fully formed and living. Their role is not simply in relationship to a main character, though it is primarily that. It’s a quality that carries over to the other “normal people” characters throughout the series. Like, I’m not sure if this experience could be exactly replicated with the diner patrons in chapter three, but at the same time, they don’t look like mannequins put in the background to fill space. Every person who appears in Murciélago looks like a person. It’s a really impressive trick that can easily fly under the radar, yet also an essential part of what makes the series work. In a narrative filled with serial killers, mass murderers, and rapists, it’s important that the world is filled with distinct individuals living their own lives. They’re not cannon-fodder or obvious future victims; if something happens to them, it matters.

I’ve also been thinking this week about superheroes, with the recent new Superman trailer. It’s just occurred to me that the argument over if superheroes should kill is directly related to their role as “crimefighters,” i.e. stand-ins for the police. Superhero stories have all but abandoned the larger societal role that they can and should fulfill to instead focus on stopping and punishing “bad guys.” It’s quick and easy storytelling, non-controversial and a good showcase for the cool powers they have. At the same time, it’s based in and reinforces false narratives about crime, intentionally or not. By reducing superheroes to consultants who handle specialty problems for the police free of charge, they are now commonly depicted in a world that we only ever see on the news. Despite how much crime levels have reduced over the decades, and how criminals aren’t, like, an inherently evil demon species we need to separate from society, both those things seem to be true in superhero comics, where superheroes can happen upon multiple violent crimes in progress every night, each one with a consciously malevolent perpetrator who wants to harm unrelated strangers.

All of which is to say, when that’s been the narrative for a long time – perhaps relevant during the crime highs of the seventies, but hasn’t been since the nineties – the conversation about what superheroes should do mirrors what people say about police and law enforcement. Namely, that being as harsh as possible and instituting the death penalty in most cases is best. Cops with Punisher logos, and people debating if Punisher counts as a superhero. And like…I could try to do a whole thing arguing for my moral position on this, but at the end of the day, I don’t know how to explain why killing people is bad. You know? At a certain point, if you can’t agree that all humans are humans, with full humanity and rights and stuff, then there’s no value in arguing over whether it’s right or wrong to kill the ones you’ve decided are bad. With the current administration kidnapping people over nothing – sometimes admittedly so – and sending them to foreign torture camps to die, I don’t think I need to explain why that punitive mindset is reprehensible. At least, I shouldn’t have to.

So yeah, I’m generally tired of people using superheroes as a metaphor for the government, especially when our view of the government is exclusively law enforcement, a.k.a. the state monopolizing the legitimate use of violence. The whole point of superheroes is that the government and other societal institutions aren’t serving the needs of the people; what if those with power did things to help us? That’s the whole game. Rather than having the villains hold all the correct critiques of society, a refreshing superhero story would put the superhero on the outside and the villain on the side of institutional authority. That’s what I liked about the new Superman trailer. While I can’t guarantee anything about the film right now, the trailer painted the picture that Superman is at odds with the world and the government because he’s acting on his own to do the right thing. Not only that, but the criticism of his actions includes the idea that if he does take action, it’s up to him to single-handedly solve all the world’s problems, despite those problems being the responsibility of government and business leaders. Like, I really loved seeing Superman get angry at the suggestion that it’s on him to solve geopolitics, instead of the leaders of the country in civil war; he did the right thing, and now we’re supposed to step up, not attack him for our failure to do so. If that holds true in the movie, then it’s going to be a really good reversal of modern superhero tropes that could reset things in a very positive direction.

To close out, I want to encourage everyone to go see Mission: Impossible: Final Reckoning (sequel to Dead Reckoning Part One). It’s seriously an incredible movie, far better than it has any right to be. It’s bold, simple, powerful, and confident. It does so many things at once, all of which work off of the same axis, and delivers on every front. So many wonderful performances, such beautifully shot and crafted scenes. A perfect movie, really. I didn’t expect to walk out wondering if it was my favorite movie ever, but here I am. Since it is a(n unnamed) part two, you should watch Dead Reckoning first if you haven’t (and if so, you’re also in for a real treat with that one). I haven’t seen most of these movies, and I didn’t feel lost with the connections to past films. It’s a very inspiring and life-affirming story that can and maybe should fail, if not for the phenomenal work put in by the whole cast and crew. It’s one giant magic trick that you’re watching unfold before your eyes. Check it out.